|

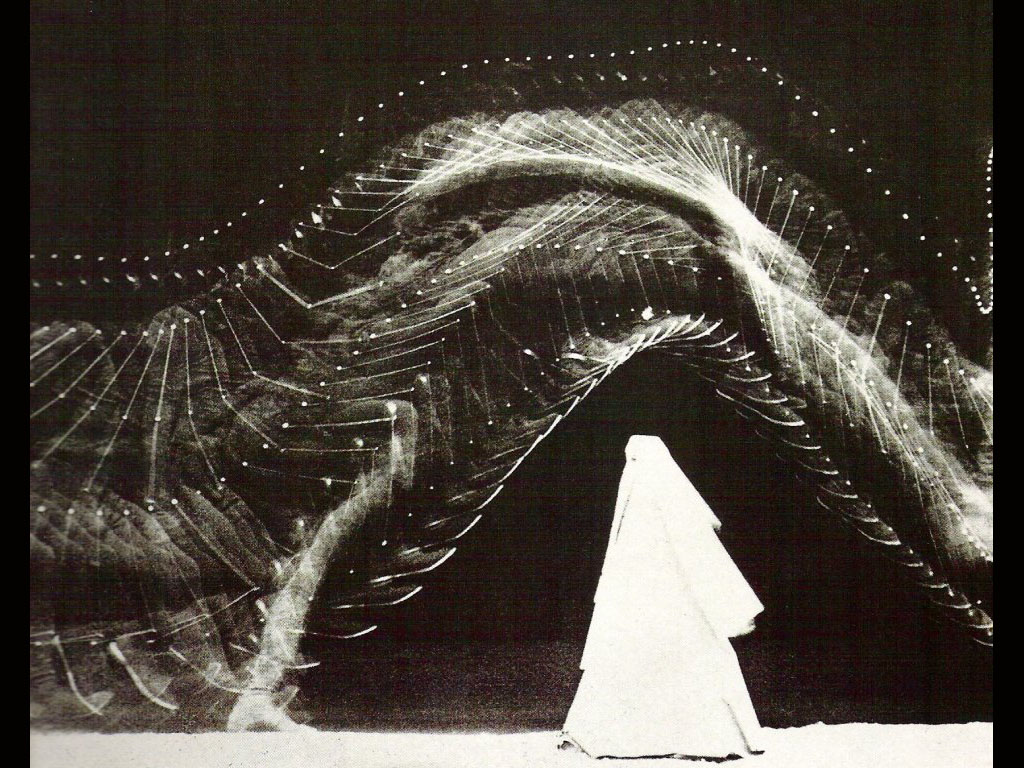

| An example of Etienne-Jules Marey's chronophotography |

From its inception there has been debate about the nature of photography. Technology and art were considered distinct categories and photography successfully blurred the line. Initially the emphasis was on the science, but as those trained in traditional art techniques began to produce photographs, the scope of photography widened.

Early debates

As Wells notes, much of this debate revolves around how ‘art” is defined. For the philosopher of aesthetics, art relates to beauty and the artist functions as a kind of seer, transcending the mere recording of events and offering an interpretation. Typically established standards of of beauty were determined by those with the power to affect production and distribution. Where this was once the landed and owning classes, today this function is carried out by curators, critics, educators, academics, and collectors.

There is disagreement among historians about when photography began to be seen as an art. One dates this to the 1880’s, several decades after the invention of the camera. Regadless of when, Wells cautions taking at face value the claims of photographers, who may or may not have wanted to be identified as artists, such as Soviet photographers who never imaged their work might one day be displayed in galleries or museums.

Realism of the mid to late 19th century was based on the conceit of unconditioned perception, of being able to create a product with a 1-1 representation of reality. The technical ability extended to the subject of depiction, focusing on everyday objects and people. One of the early uses of photographs were as reference notes for painters. Photography reinforced the idea of perspective developed in western painting and added to the mix a sensitivity to focus. While photography released painting from literal depiction, it encroached in many ways on its traditional territories. Portraiture was now available to most anyone, art objects from far away places could be brought near through photographs, and photos themselves could mimic the conventions of paintings.

In the 1890’s a group of photographers broke away from the Photographic Society of Great Britain to pursue more artistic, and less scientific, concerns. They called themselves the Linked Ring Brotherhood. They were one of several such movements across Europe and the US looking for new opportunities of artistic expression using camera technology. Stieglitz was a member of the Brotherhood and did much in the US to promote art photography, including publishing the magazine Camera Works and organizing numerous exhibits. Wells sees this as part of the overall trend in the arts at this time, which saw the arrival of impressionism in painting, naturalism in theater, and the beginnings of cinema. It was a period of economic, social, and intellectual ferment.

One of the more interesting paragraphs in this chapter is on the development of exhibition standards. Traditionally, lighting was poor, mounting was largely ignored, images were hung literally floor to ceiling. During this period images began to be framed and mounted more uniformly, more wall space was allocated to each image, and images were removed from the lower and upper ends of the wall.

The Modern Era

The Modern movement was based on the idea that art has formal properties of shape, color, texture, shape, and size. Wells cites critic Raymond Williams (When was Modernism) that though modern was first used in mid-19th cent, it came to refer in the 20th century to a series of avant-garde movements. Several factors are held to account, including political and economic ferment creating a climate of uncertainty, the migration of people (including artists), growth of publishing, and the internationalisation of the arts. The artist was seen as someone offering an outsider’s perspective. Wells also cites critic Clement Greenberg who believed [in what appears a contradiction] that while art is free of social context, it was the artist’s job to preserve and advance culture in the face of mass produced, capitalist kitsch.

“Broadly speaking, modern photography sought to offer new perceptions, literally and metaphorically, using light, form, composition and tonal contrast.” (p275) Quotes Peter Wollen (1982) on the passing of pictorialism and the emerge of the new machine aesthetic emphasizing brilliance, sharpness, clarity, and precision. The art of discovery replaced the art of invention. Wells continues with a discussion of three modernist movements: Soviet Constructivism, American Formalism, and the Surreal.

Constructivism emphasised the depersonalisation of art in the exploration of rules governing artistic communication. Photography was seen as an ideal art as it is more mechanical in nature and thus less susceptible to individual influence. It was also seen as more democratic and thus more true to principles of socialism. American formalism was also concerned with the properties of visual communication but completely unconcerned with politics or economy. It is perhaps best remembered as a movement concerned with perfection in technique. One of its more famous exponents, Edward Weston, described his work as both abstract and realist: the former from a concern with form, composition, and tone, the latter with precision focus and printing. Unlike other movements which eschewed the bourgeois character of the art gallery, formalists sought it out. Where the label Am Formalism is retrospective, Surrealism was a manifesto movement. It attempted to recreate dream states, to disorient the viewer and thereby break down barriers between external and internal experience. Surrealist photography stressed the imagination as a source of insight into experience and used techniques such as montage, rayographs and solarisation. Critiques have emphasised that the surreal is not a kind of image but a kind of meaning based in enigma. The cognitive shock of a surreal image is thought to rely on the subversion of the transcriptive power of the photograph. Feminist critiques have noted the continued objectification of the female body.

Late 20th Century Perspectives

By the middle of the century media were graphically oriented, artists began to engage socially and politically, and postmodern theory became an influence on the making and reading of images. Where Modernism focused on the medium, Conceptual Art stressed ideas, especially those focusing on the vocabulary of expression and contexts of interpretation. Quotes Campany (2003): “every significant moment in art since the 1960s has asked, implicitly or explicitly: ‘What is the relation of art to everyday life?’” In education, new degrees in photography emerged which did more than teach technique but inquired after semiotics, or how images are read. Where straight and documentary had been the predominant style since before WWII, by the 70’s conceptual approaches led to construction, or previsualization, in the service of concepts.

Wells notes the 70s emergence of feminism and its impact on art. She finds feminism operating on three fronts: an examination of female representation in western art, the search for and presentation of "lost" female art, and the demand for representation of female art in contemporary space such as galleries, museums, and publishing. She cites three seminal UK exhibitions of the 1980s focusing on female photography.

In addition to women finding a new voice, many marginalized people began to find avenues of expression to explore ideas of black, Latino, Asian, and immigrant identities. No mention here of homosexual, lesbian, or transgender identities.

Photography within the Institution

This is perhaps the most difficult section of the chapter to summarize. Wells begins by emphasizing the difficulty of assessing current trends. She notes the declining influence of the gallery and the importance of the photography book, but clearly this was in the period before wide penetration of the internet and mobile services. She discusses the role of the curator, seen by some as a creative role in its own right in being able to shape public consumption and tastes. International photography festivals have since the 80s come to be important events for bringing together talent, shaping trends, and promoting photography as an art. Many schools now teach photography as an art, and many aspiring photographers are now committed to working as an artist (rather than, say, a journalist or documentarian).

The chapter concludes with a case study of Landscape photography.

I found this the least interesting chapter of the book, possibly because aesthetics is not a topic that inspires clear, lucid writing. It may be, too, that because I’m at the end of the book and the end of the course, I don’t have as much patience as I mighjt otherwise.

No comments:

Post a Comment